When gasoline prices start to rise, the public certainly takes note. However, although consumers grouse over the cost of gas, and even search for a source to blame, most people have very little idea of how these prices come about. Here we'll take a look at the factors that determine the price consumers pay at the pump – and "Why You Can't Influence Gas Prices" (as an individual).

Oil Prices: The Crude Reality

Most people believe the price of gasoline is determined only by the price of oil. Obviously, the two are linked – for statistical details, see Understanding the Oil & Gas Price Correlation – but overall, it's a bit more complicated than that. While oil is important, a whole host of factors impact the average retail price of gas.

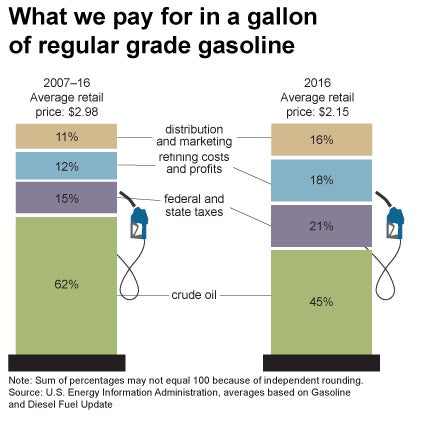

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the price of crude oil comprised 59.4% of the average retail cost of gasoline in January 2018 (the latest available figure). Federal and state taxes were the next highest cost factor, averaging 18.3%, followed by refining costs and profits, then distribution and marketing.

Between 2007 and 2016, the price of crude oil averaged 62% of the average retail cost of gasoline. Federal and state taxes were the next highest cost factor, averaging 15%, followed by refining costs and profits, then distribution and marketing.

To help understand how gas prices are set, it helps to examine supply, demand, inflation and taxes. While supply and demand get the most focus (and the most blame), inflation and taxes also account for large increases in the cost to consumers. (To learn more, read "How Does Crude Oil Affect Gas Prices?")

Supply and Demand

The basic rules of supply and demand have a predictable impact on the price of gas. (For background, check out our Economics Basics tutorial.)

Supply

Oil does not come out of the ground in the same form everywhere. It is graded by its viscosity (light to heavy) and by the amount of impurities it contains (sweet to sour). The price for oil that is widely quoted is for light/sweet crude. This type of oil is in high demand because it contains fewer impurities and takes less time for refineries to process into gasoline. As oil gets thicker, or "heavier," it contains more impurities and requires more processing to refine into gasoline.

Light/sweet crude has been widely available and sought after in the past, but is becoming harder to obtain. As the supply of this preferred oil becomes more constrained, the price climbs. On the other hand, heavy/sour crude is widely available through out the world. The price of heavy/sour crude is lower, sometimes substantially lower, than light/sweet crude, to compensate for the higher capital investment it requires to process.

Demand

Change in the demand for gasoline is primarily set by the number of people who are using the fuel for transportation. The growth in the number of people driving cars and trucks, particularly in parts of the developing world, has expanded dramatically in the last few years. China and India, each with a population in excess of one billion, are experiencing an expanding middle class that will likely drive more cars and use more gasoline over time.

China is building 42,000 miles of new interprovincial express highways to accommodate the all the new car sales in that country. By comparison, the U.S. has about 86,000 miles of interstate highways. India has plans to construct another 12,000 miles of expressways by 2022. Cars driving on those highways are going to consume more gasoline, creating more demand for fuel. (Read about how industrialization can be good news for your portfolio in "Build Your Portfolio With Infrastructure Investments.")

Many countries subsidize the retail price of gasoline to encourage industrial development and to gain the popular support of the people, creating an artificially higher demand for gasoline. Changes in this subsidy will affect the demand for gas similarly to price increases or price decreases.

Creating Balance

Prices help to allocate scarce goods. Although demand for gasoline is more elastic in the long term, small disparities in supply and demand in either direction will have a large impact on prices in the short run. This inelasticity of demand means if prices go up, demand goes down, but not by very much.

The problem is that people are locked into their lifestyles for the near term. While they can change their fuel consumption by buying more fuel-efficient vehicles (see "Hybrids: Financial Friends or Foes?"), moving closer to work, and/or taking public transportation, they can't or won't do so in response to a temporary hike in prices – so the effects aren't immediate.

Price will balance supply of gasoline with demand, and the global market for gasoline provides the forum for establishing that balance.

Inflation and Taxes

Inflation and taxes account for the biggest relative increases in the price of gasoline.

Inflation

Inflation is the general rate at which prices of goods/services are rising (and, conversely, the rate at which purchasing power is falling). In the U.S., an item that cost $1 in 1950 would cost about $10.45 in 2018. In 1950, gas cost about 30 cents per gallon. Adjusting for inflation, a gallon of gas should cost about $3.13, assuming taxes, supply and demand stayed the same. The level of inflation varies by country, which can influence the price of fuel. (To learn more, read our All About Inflation Tutorial.)

Taxes

The tax on a gallon of gas in 1950 was approximately 1.5% of the price. In January 2017, the federal, state and local tax on a gallon of gasoline was 19.5% of the total price. This means that taxes added about 48 cents to the price increase in a gallon of gas. Federal tax made up 18.4 cents, state tax made up 27.3 cents, and local and other taxes made up 4.3 cents per gallon. Other countries have vastly different tax policies for gasoline, some of which can make taxes the largest price component.

Cumulative Effects

As a point of reference, inflation and taxes added approximately $2.83 to the rise in the price of gasoline over the 58-year period from 1950 to 2008. It is important to have this perspective when considering the impact of supply and demand on the price of gasoline.

The Bottom Line

Over the short term, as prices rise or fall, demand for gasoline tends to be relatively inelastic. People only make small changes in their consumption when there are large changes in the price, and this pattern helps balance the supply and demand of gasoline.

Over time, we can expect to see a movement toward lower fuel consumption at the individual level, but an increase in the number of people who depend on gasoline worldwide. These changes will no doubt impact the price we pay at the pump.

While there is a common belief that the price of gasoline is solely determined by the supply and demand of crude, several other important factors come into play as well. Taxes, depending on the country, can add substantially to the retail price of gasoline. Over time, inflation also results in higher gas prices.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/options-lrg-4-5bfc2b2046e0fb0051199e91.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/oil_pump_ap0709190103214-5bfc36e146e0fb0051c07a60.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/etfs-lrg-2-5bfc2b23c9e77c00519a9390.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/thinkstockphotos-178882579-5bfc352246e0fb00265db9a8.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/4-benefits-of-rising-oil-prices-5bfc2df546e0fb0083c0e7af.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/will_winter_affect_the_price_of_oil_and_gas-5bfc342ec9e77c0051458862.jpg)